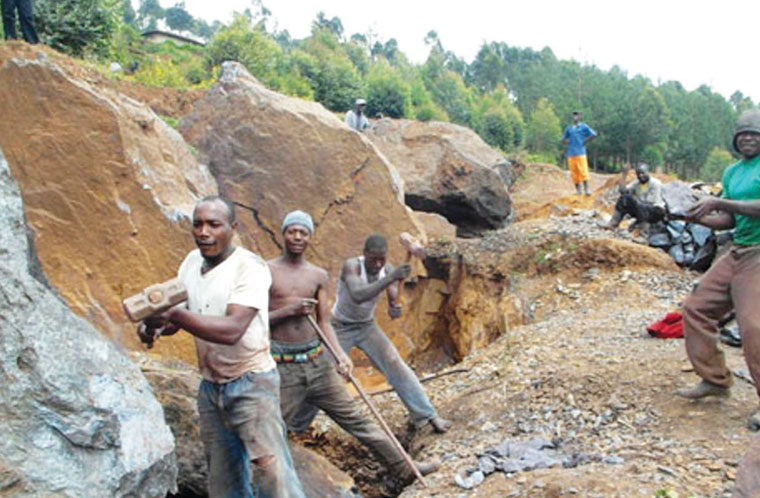

About ten years ago if you had a chance to ply the Kabale-Kisoro road you would find piles of iron ore scattered by the roadside along the entire journey from Kabale to Muko High School playground that used to be the major loading site for trucks during that time. Iron ore had become a quick cash cow for many families in this region whose main economic activity at that time used to be Irish potato farming.

Many that had discovered mountains of this beautiful black shiny rock ‘whose shininess can pass for a gem’ in their backyard or farms, were minting money with a 3.5ton truck going for about shs.80000 everyone who had a chance was cashing in and it was all fun and merry for every young man that could ply the trade until the government come in and imposed an Iron ore export ban in February 2015. The reason that was given for this export ban was that the locals were being reaped off and only getting pennies on a dollar for what’s worth and this was the spin-off event that led to the mineral export ban spilling over to all other minerals in the sector.

Government’s reasoning at that time seemed to be pro-people but it was not aligning with the economics of the trade. Luckily in 2013 when the international iron ore trading price was 130$/t, I and two friends of mine got a sweet deal to supply iron ore to a prominent old businessman in Nairobi and we were all excited and blinded by the overall contract value which was in millions of dollars and off we rushed to the beautiful hills of Muko and started buying and loading iron ore in truck loads off to Nairobi without critically looking at the numbers.

A few weeks down the road we realized that transport was eating up all the money with returning trucks charging up to 80$/t to Nairobi it was hard to breakeven and we decided to negotiate with Uganda railways which gave us a piling yard at it’s Good-shade where we stockpiled the iron ore we planned to reload onto wagons that would move the material to Nairobi. While we were still struggling to stockpile material at good-shade our buyer in Nairobi went mute and to-cut the long story short, the old man and his agent swindled us of all our monies and we end up running back to Kampala indebted and licking our wounds.

What had begun as an exciting business venture ended up being a disaster and its only later on when a friend of mine took me to meet an old rich Indian businessman in Mombasa who owned an iron ore mine in Tsavo at the time and had had a keen interest in setting up his own steel plant in Kabale that I realized why the Nairobi man had vanished.

The old Indian Businessman had done his own feasibility study about Kabale iron ore and he also explained to us why one steel plant in Jinja at the time was having a challenge breaking-even processing the iron ore from Kabale but that’s a story for another day. In his truck yard laid about 100 tons of iron lumps from Kabale despite the fact that he had an iron ore supply deal with Bamburi cement at the time.

We discovered that the transportation of iron ore alone from Kabale to Mombasa was more than 100$ per ton making the total cost of the ore landed in Mombasa more than the cost of iron ore on the world market. It’s on this trip that I discovered iron ore could not be containerized and any hope of Kabale iron ore getting to smelters in China or India could only be done by a sea vessel. The smallest sea vessel that we could chatter was a 20,000 tonner meaning we had to transport over 700 trucks of iron from Kabale to Mombasa, hire a stockpiling yard at Mombasa Port for the iron and later use bulk loading facilities which Mombasa didn’t have to load the iron ore onto the sea vessel.

After this trip we humbly come back home knowing that Kabale iron ore will never see furnaces in China or India and the furthest it can ever go is Nairobi mainly because of the logistic costs involved.

Recently, there has been an iron ore rush in the Kigezi region because of the iron export permit that was issued to a Kenyan company. A number of businessmen have been ploughing the mountains of Kigezi looking for areas with iron ore potential with hopes of cashing in on the huge demand of the ore in Kenya. The big question is, does it make sense to ban the export of iron ore or create a monopoly around the trade? the answer is no and this is why.

Transportation of iron ore in the country can be done with trucks specifically bought to transport the ore from Kabale to Tororo’; and still be able to break even. If you want iron ore to be transported beyond borders, you only have to use Kenyan trucks that are making a return journey and these trucks are limited in number. We can barely export 250000 tons per year meaning it would practically take us 10 years to export 2.5 million tons of iron ore to Kenya out of the 200 million tons we supposedly have.

Therefore, it doesn’t make business sense to use the export ban to limit the export of a product that’s already limited by its own logistics. Keep in mind that if the logistics become costly with a monopoly already in place, miners will be forced to sell their iron ore cheaply because they have no alternative and this defeats the logic the government had used to impose the ban in the first place.

Government banned the export of iron ore because it wanted local value addition and the establishment of a smelting plant in the Kigezi region. Tembo Steel in Iganga has dealt with the local value-addition aspect and it has done an outstanding job of succeeding where others have failed and this also inspired the reopening of the Jinja Steel plant that had been closed for years. The success of these two plants is definitely a ray of hope in many aspects for the mining sector in Uganda. However, the consumption of these 2 plants is barely 800 tons of ore per day therefore with our reserves of over 200 million tons it would take them over 500 years to exhaust at the current rate.

Going back to the Kigezi region, the question is why have many investors failed to set up steel smelting plants at the source of the iron ore itself and here is what many think. One of the biggest challenges is the energy costs when smelting iron ore, the nearest source of an active coal mine is the Ruvuma coal mines in Tanzania which is more than 2000km away from Kabale. Coal is not only used for fuel but also in the oxidization process of iron ore therefore, we need coal in Kabale even if we decide to use an alternative source of power.

Alternatively, a gas pipeline from Hoima to Kabale which would cover about 500km could locally be the best or cheapest source of fuel to power an iron ore furnace but that still seems to be many years from today. A third alternative is the Lake Kivu methane gas. Lake Kivu gas is only 230km from Kabale making it much shorter than the Hoima source. A methane gas pipeline from Lake Kivu to Kabale would go a long way in helping to solve the energy costs in Kabale

Finally, studies have shown that export restriction measures of raw materials deployed by governments do not promote local value addition or improve government revenue as hoped. A case in point is that of the chromium industry in Zimbabwe. In 2012 the Zimbabwe government banned the export of chromium concentrates with hopes that it would boast the local ferrochromium sector. This ban made chromite ore so cheap forcing all the big and small miners to suspend production and some running bankrupt, in short, the ban was a disaster for the industry.

Therefore, the export ban in Uganda has been a disaster for the entire mining sector and it’s going to take some time to get back to where we used to be. The best thing government can do for the over 10,000 jobless artisanal miners deep in the hills of Kigezi is removing the export restrictions on iron ore.

The writer; Agumya Allan ([email protected]) is the the Vice-Chairman Miners’ Forum Uganda

If you would like your article/opinion to be published on Uganda’s most authoritative news platform, send your submission on: [email protected]. You can also follow DailyExpress on WhatsApp and on Twitter (X) for realtime updates.