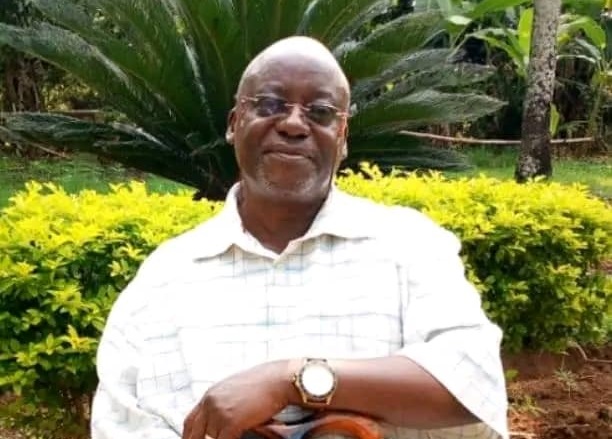

By Oweyegha-Afunaduula

The idea of Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM), like the idea of Integrated Pest Management (IPM), was conceptualised in the 1970s as a way to improve the growing complexity of water resources management and to enhance the participation of civil society, as local communities, community-based organisations (CBOs) and nongovernmental organisations (NGOs), in managing water resources (Both Ends and GETSD, 2011).

That was the time when the idea of integrated knowledge production was also emerging, in Europe mainly. I was introduced to both IWRM and IPM when I joined the University of Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania, in 1972 for undergraduate studies in Zoology, Botany and Geography with Development Studies. That academic background was to be pivotal in my higher studies in the field of The Biology of Conservation at the University of Nairobi, Kenya, from 1980 to 1983 for a Masters degree in Zoology.

The ideas of IWRM and IPM re-emerged in my academic, intellectual and professional development at the University of Nairobi in the area of environmental management and conservation. However, there was no evidence that the University of Nairobi had accommodated the wind of change in knowledge production in global education, which at that time favoured alternative knowledge production via mainly interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity.

Although The Biology of Conservation resourced instructors and/or knowledge workers from across the university curriculum, it was not an integrated programme of study. It is best described as a multidisciplinary programme. It allowed knowledge workers and/or instructors from different disciplines and professions to participate in it, but did not allow for integration and, therefore, did not challenge disciplinarity.

To challenge disciplinarity, it should have been interdisciplinary, cross-disciplinary, transdisciplinary or extra-disciplinary. It was not surprising that the designers of The Biology of Conservation programme made it multidisciplinary. That was the time criticism of strict disciplinarity was beginning to be widespread and multidisciplinarity was emerging because the academia tolerated it as it was not antagonistic to disciplinarity.

Therefore, the Department of Zoology at Chiromo Campus of the University of Nairobi was just the physical, academic and administrative home of the programme and receptacle of knowledge workers, professionals and instructors from multiple disciplines, departments, faculties of the university to make The Biology of Conservation programme adequately multidisciplinary.

Many other Universities across the globe also started to conduct their Biology of Conservation programmes, which were called Conservation Biology programmes. Makerere University did not introduce Conservation Biology until the early 1990s when I served as one of the instructors in the Faculty of Science.

At the University of Nairobi, The Biology of Conservation was organised into four broad areas: Ecology, Natural Resources Management and Conservation, Ecological Techniques and Computer Science. Courses included Remote Sensing Techniques, Soil Science, Climatology, Bioclimatology, Behavioural Science, Natural Resources Management, Conservation, Research Methods, Political Science for Conservation Biologists, and Social Science for Conservation biologists. The latter two explain why, although a natural scientist, I am comfortable integrating the humanities and social sciences with the natural sciences and engaging political considerations in my writings and intellectual discourses.

This background information is important to indicate to you why I am interested in integrated knowledge production, integrated pest management and integrated water resources management. Having come from a field that required multidisciplinary participation and cooperation of knowledge workers, professionals and practitioners from across the board, the idea of integrated water resources management attracted me and meant a lot to me because professionally I started off as a fisheries research officer (Biological Oceanography) in the East African Marine Fisheries Research Organisation (EAMFRO) of the Eat African Community (EAC) and based in Zanzibar.

In this article my thesis statement is: “Integrated Water Resources Management is best achieved through a Negotiated Approach (NA) rather than a Command-Obey Approach (COA) from the top”.

In Uganda today, virtually everything is managed by applying COA with the President of Uganda, Tibuhaburwa Museveni, at the centre. The NA has been reduced in significance, accompanied by de-professionalisation. Considerations such as political loyalty, kinship, technical know-how, although frequently condemned by power, weigh more than knowledge, professionalism, experience and wisdom in the management, governance and leadership of natural resources and all sectors of the economy. Corruption and nepotism are inevitable, water resources management has not been spared. This has meant that integrated water resources management is more talked about than actualised.

In any case integrated natural resources management can not be achieved if there are no professionally produced integrators in charge. Such actors can be produced at our institutions of higher learning if integrating sciences – interdisciplinarity, crossdisciplinarity, transdisciplinarity and extradisciplinarity – are institutionalised at our university campuses.

Only Mbarara University of Science has accommodated interdisciplinary science, but there are rumours that the authorities there want to terminate the science. All other universities are ignorant about the new and different sciences.

Therefore, even if we advance the Negotiated Approach its effectiveness will be difficult without integrated and integrating universities producing for us people who are not limited by disciplinarity considerations, love genuine teamwork, are future-ready professionally, and can integrate ideas, strategies and practices, are free to engage in critical thinking and alternative analyses without fear or favour and can discard their entrenched disciplinary biases for the good of IWRM).

Even then there is a need to have a cadre of political leaders who do not easily recourse to COA to push their own choices and agenda in the water sector. Such leaders wil be knowledgeable about the value of integration in general and IWRM in particular. We are far from having such leaders because our universities are not producing them.

I have a feeling that some of my readers may be asking “But why hasn’t this man explained to us the real definitions of IWRM, NA, COA? How shall we judge that IWRM is a good thing for our waters? How shall we conclude that NA is a better approach to IWRM, yet we have seen COA achieving beneficial results in some countries? Isn’t NA time-consuming?”

Well, questioning is always good because simplicity can be dismissed and complexity confronted in a world which is not simple but complex. COA ignores complexity and exploits simplicity, but this makes the complex even more complex and introduces problems for which we have no answers because we were not prepared for them.

Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM)

Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) has been widely accepted as the water management regime for the 21st century. Despite extensive publications on IWRM as well as the establishment of the necessary enabling environment globally, implementation remains elusive (e.g., Jonker, 2007).

IWRM is a process that aims to develop and manage water, land, and related resources in a sustainable way. It is based on the idea that water is a natural resource that is also an economic, cultural and social good, and a vital part of the ecosystem. It promotes the coordinated development and management of water, land and related resources in order to maximise economic, social and cultural welfare in an equitable manner without compromising the sustainability of vital ecosystems. Its basis is that the many different uses of finite water resources are interdependent. It has the potential to ensure water security for humanity in the 21st century and beyond despite the threat of climate change, which in a way has to do with mismanagement of the water resources.

IWRM approaches include:

- Integrating domestic, agricultural, industrial, and environmental needs into water catchment management

- Encouraging participatory processes that include all groups of water users

- Emphasizing the role of women in water management

- Balancing economic efficiency, ecosystem sustainability, and social equity

Activities to promote IWRM include:

- Preventing, controlling and reducing transboundary impacts, as defined in the Water Convention

- Promoting the ecosystem approach in the framework of integrated water resources management

- Promoting equitable and reasonable utilisation of transboundary waters

Further goals of IWRM are to:

- Advance adaptation to climate change in the transboundary context, including flood and drought management

- Promote understanding of the water-food-energy-ecosystems nexus and the reconciliation of multiple water uses in transboundary basins

- Advance the understanding of the benefits of transboundary cooperation;

- Prevent accidental water pollution

- Facilitate the financing of transboundary water cooperation

- Facilitate reporting under the Convention and on Sustainable Development Goal indicator 6.5.

- Ensure conservation and, where necessary, restoration of water-related ecosystem

Water management locally, regionally and globally has changed a great deal, especially from the beginning of the New Millennium with the advent of globalisation. Uganda was the first country in Africa to embrace globalisation as its pathway to development. This has had dire consequences to the management and use of her natal resources such as water.

Locally in Uganda water management has become more and more presidentially determined, with the Command and Obey Approach at its centre. What was for centuries a social and cultural good is now financialised and monetised and is increasingly becoming de-culturalized and dissocialised as the preferred water governance is the exclusion of the local communities from water management and governance.

Regionally water management has been placed under the Nile Basin Initiative (NBI), a grouping of the countries of the Nile Basin, ostensibly for the socioeconomic development of the region. However, the NBI has not innovated any new approach other than the business-as-usual approach fuelled by the international financial institutions (IFIs). Although NBI has a Nile Basin Sustainability Plan (NBSP) its preference of large infrastructure occludes sustainable water management, integrated Water Resource Management and the effective management of local Nile Communities.

Globally, water management is now more of a preoccupation of global institutions mostly committed to dispossessing and displacing the local communities from freshwater bodies, or resources, mainly from the construction of big and large dams for electricity. As I stated above International Financial Institutions (IFIs) are preoccupied with financialising and monetising fresh water at the expense of the cultural and social resources of the local peoples and communities.

According to Jonker (2007), there is need for a different conceptualisation of IWRM. It is not primarily about water, but essentially about people. Based on this, the definition of IWRM (if we must have a definition) could be changed to put people at the centre and then relate people’s activity to water as demanded by Merrey et al. (2005). A definition could be: IWRM is a framework within which to manage people’s activities in such a manner that it improves their livelihoods without disrupting the water (Jonker, 2007).

Negotiated Approach Water Management

A negotiated approach is a discussion between two or more parties that aims to reach an agreement through bargaining. The term “negotiate” means to deal or bargain with others to arrange or bring about something through discussion and settlement of terms.

When applied to water the Negotiated Approach (NA), as it reads, involves negotiating decisions and strategies to manage water for the benefit of all. Its aim is to strengthen integrated water resources management (IWRM) by involving the local citizens and/or communities, and stimulating and enabling them to co-manage their immediate environment and improve their own livelihoods. It stands for the meaningful, effective and long-term participation of local stakeholders in all actions and practices in water resources management (see also Both Ends and GETSD, 2011).

One essential aspect of the approach is that negotiations are viewed as a process of involvement in which participants increase their collective knowledge, wisdom and understanding as well as their capacity to solve problems to serve a common (public) interest. Negotiations, therefore, refer to participation through open, flexible and creative interactions in which all stakeholders enjoy equal rights and opportunities to play their part in finding solutions to the challenges they face. The solutions should reflect their different interests and ensure that the benefits are optimally shared (see also Both Ends and GETSD, 2011).

We can conclude that the negotiations, as a process in NA, will ensure that local stakeholders are included in, not excluded from, IWRM. Top-down domination and control of water management is an antithesis of IWRM.

Command and Obey Approach to Water Management

Command and Obey Approach (COA) to water management is the exact opposite of NA approach to water Management. It relies on centralisation of power and authority. In Uganda, the Uganda Constitution 1995 placed all power and authority in the hands of President Tibuhaburwa Museveni, who has ruled the country since 1986, when he captured the instruments of power through the gun, and has retained power since 1995 through militarily supervised elections every five years to ensure that no alternative leader emerges.

H.E. single-handedly makes all the key decisions, including the management of natural resources such as water and minerals (including oil, rare earth minerals and fisheries) and unnatural resources, as well as agricultural resources such as oil palm and coffee. He uses the COA to exclude NA, and thus the local citizens, even their elected representatives in the Parliament of Uganda. When citizens seek redress in the courts of law the President declares that “Uganda does not belong to Judges and lawyers).

As far as the management of water in Uganda is concerned, the President decreed that the waters are in the hands of Uganda Peoples Defense Forces or the soldiers, ostensibly to ensure that the people do not abuse fisheries using unsuitable nets. Meanwhile, he permitted mainly foreigners to establish fish cages along the coastline and further on Lake Victoria to make money. This effectively excluded the local citizens and their fishing communities from the waters such as those of Lake Victoria.

More specifically it has destroyed the cultural, ecological and biological ties of the communities to the lake and their time-tested local water management regime. It is unlikely that IWRM can meaningfully be implemented in Uganda under the presidentially militarily dictated and determined water management regimes.

Way Forward

Ugandans need to critically evaluate the commands given to them and to speak up if they believe that they are being commanded to do something wrong. Other wise following without thinking critically and reasoning wil end up being the main reason why mismanagement of water resources will continue to prevent Integrated water resources management from the totality of national resources management in Uganda to our detriment.

People must organise not agonise. They must insist on negotiating their role and position in the management of their water resources, instead of leaving the President to decide and do everything. Civilised management of water resources in the 21st Century and beyond is IWRM. Anything else is diversionary and serves the interests of those who do not own the water resources.

Besides, Hierarchical systems subserved by the Presidential System of political governance, are no longer fashionable but persist. With the World Wide Web (internet), such systems are negative forces against integration and have no meaningful role any more in a human society yearning for effective participation and cooperation in the management of resources involving all stakeholders. IWRM cannot work in Uganda under presidential arbitrariness, which is increasingly undermining institutions. It can only be pronounced in official documents and speeches.

For God and My Country.

Do you have a story or an opinion to share? Email us on: [email protected] Or join the Daily Express WhatsApp channel for all the latest news and trends or join the Telegram Channel for the latest updates.